Standing at the building entrance for my first job interview in weeks, sweat beaded at my brow. Yes, I was anxious about this interview, but I was also scared. Would they find out my secret? Were my things safe? Would they be there when I got out? What if I lost everything? Was even trying to get hired worth it?

I have never been in this scenario, nor had to ask any of these questions, but thousands do every year in Austin. Homelessness is a difficult experience many of us cannot fathom.

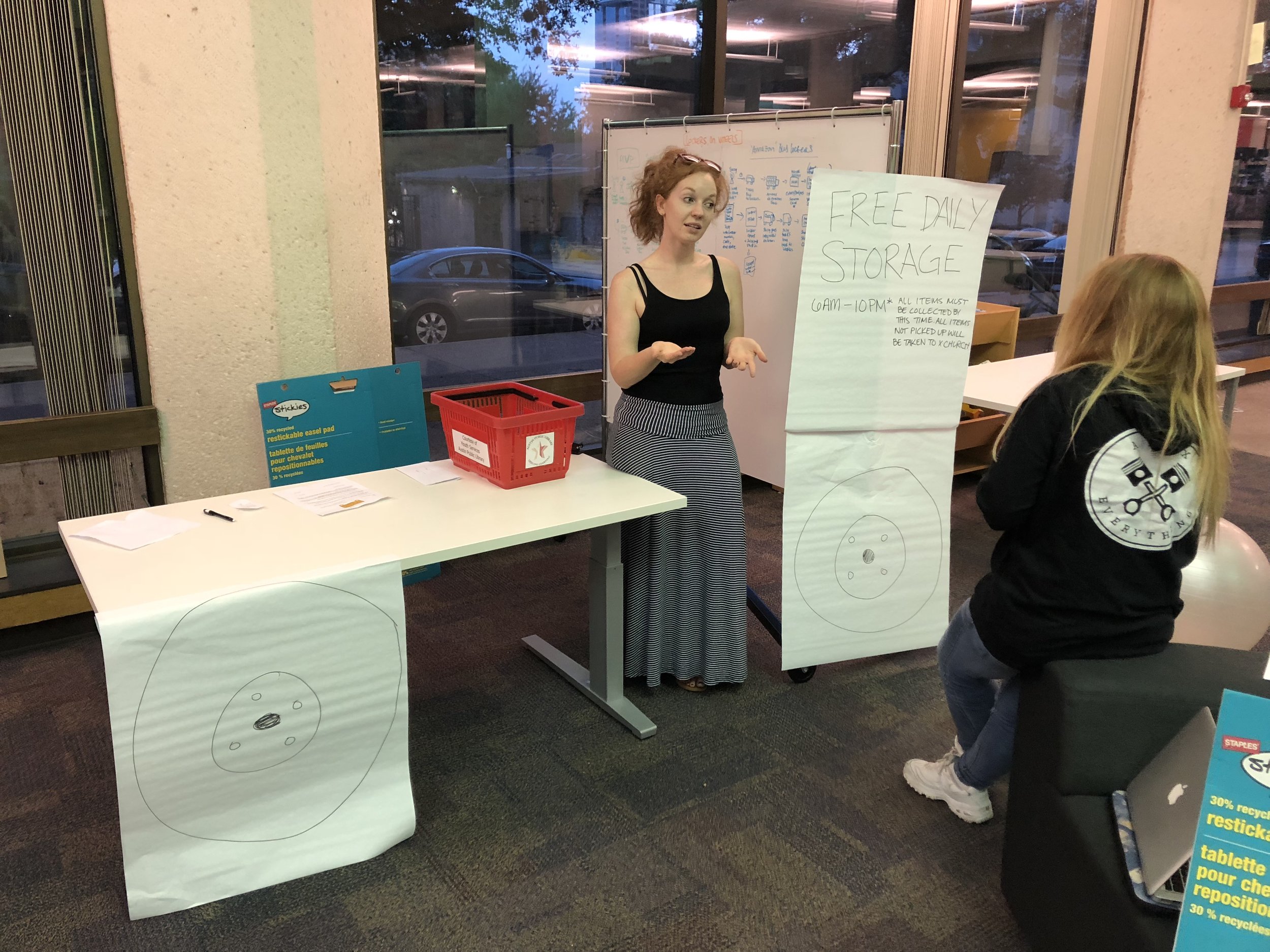

This past weekend, the City of Austin Innovation Team and Service Design ATX Meetup group hosted the Service Hustle for Homelessness, a three-day co-creation workshop with volunteer design professionals and people with lived homelessness experience in their present or past. Months prior to this workshop, the hosting team gathered insights along with the Housing Authority of the City of Austin (HACA) through over 120 user interviews to understand the key issues facing Austin’s homeless population.

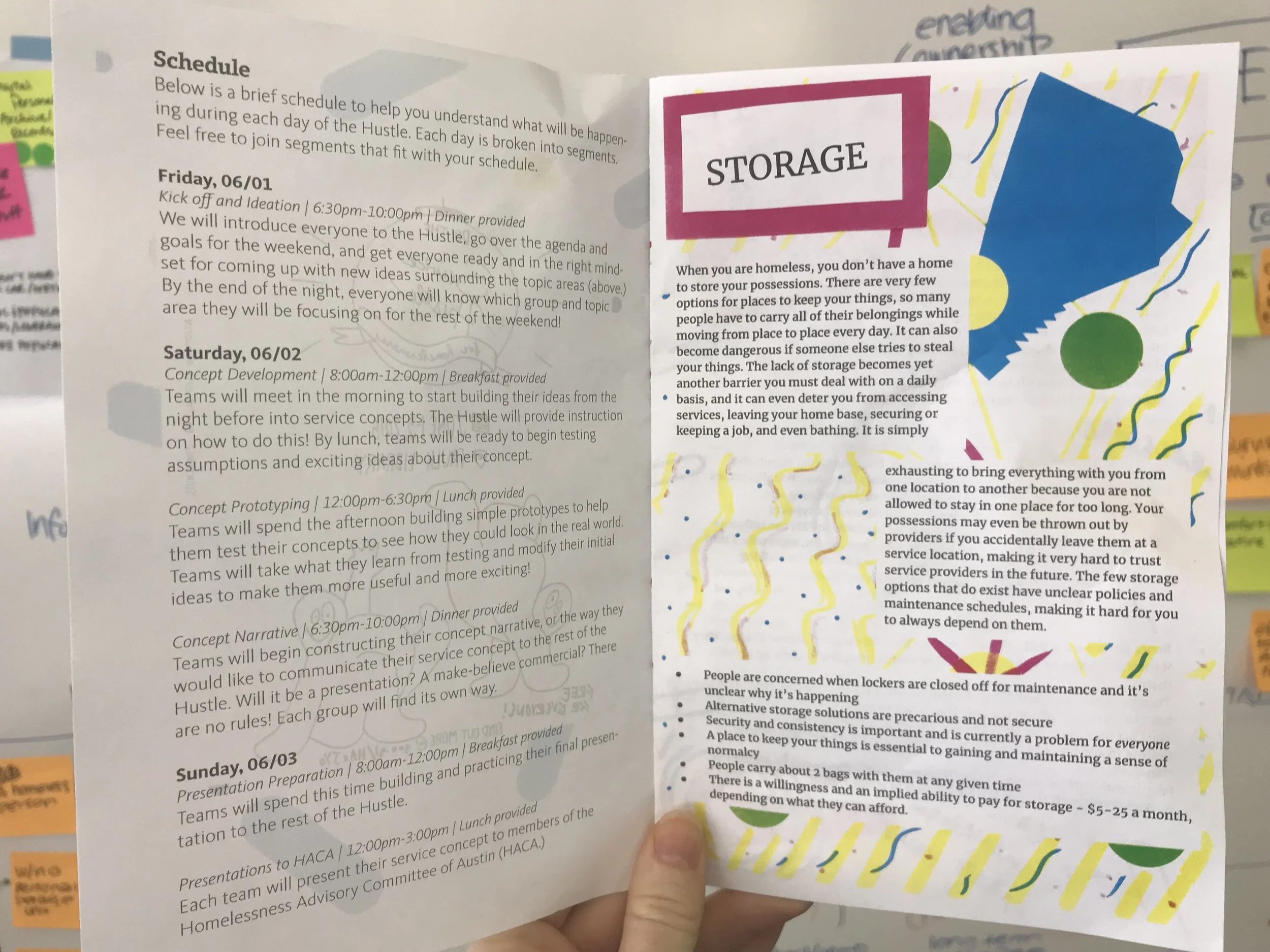

Research booklet prepared for the weekend event

Storage was the target chosen by my team from the research options presented and through it, we began to understand more what the homeless population in Austin faces.

Access is limited. With just a bedroll, you cannot enter the Austin Public Library. You are identified as homeless and treated differently by businesses. Going to a job daily is a challenge.

Security and safety are table stakes. As a homeless person, I very well may carry everything precious to me, including my birth certificate and the only nice interview outfit I own, as well as food for the next couple days. Without a place to leave this while I try to improve my situation or experience a bit of relief from the streets, I am relegated to hiding in wooded areas or leaving outside buildings, hoping it isn’t stolen or disposed of by the city.

After Friday’s dinner of catered barbecue and a round of co-creation on key issues, groups formed around top ideas; I joined the team using the starter idea of “storage leveraging the city’s unused spaces.”

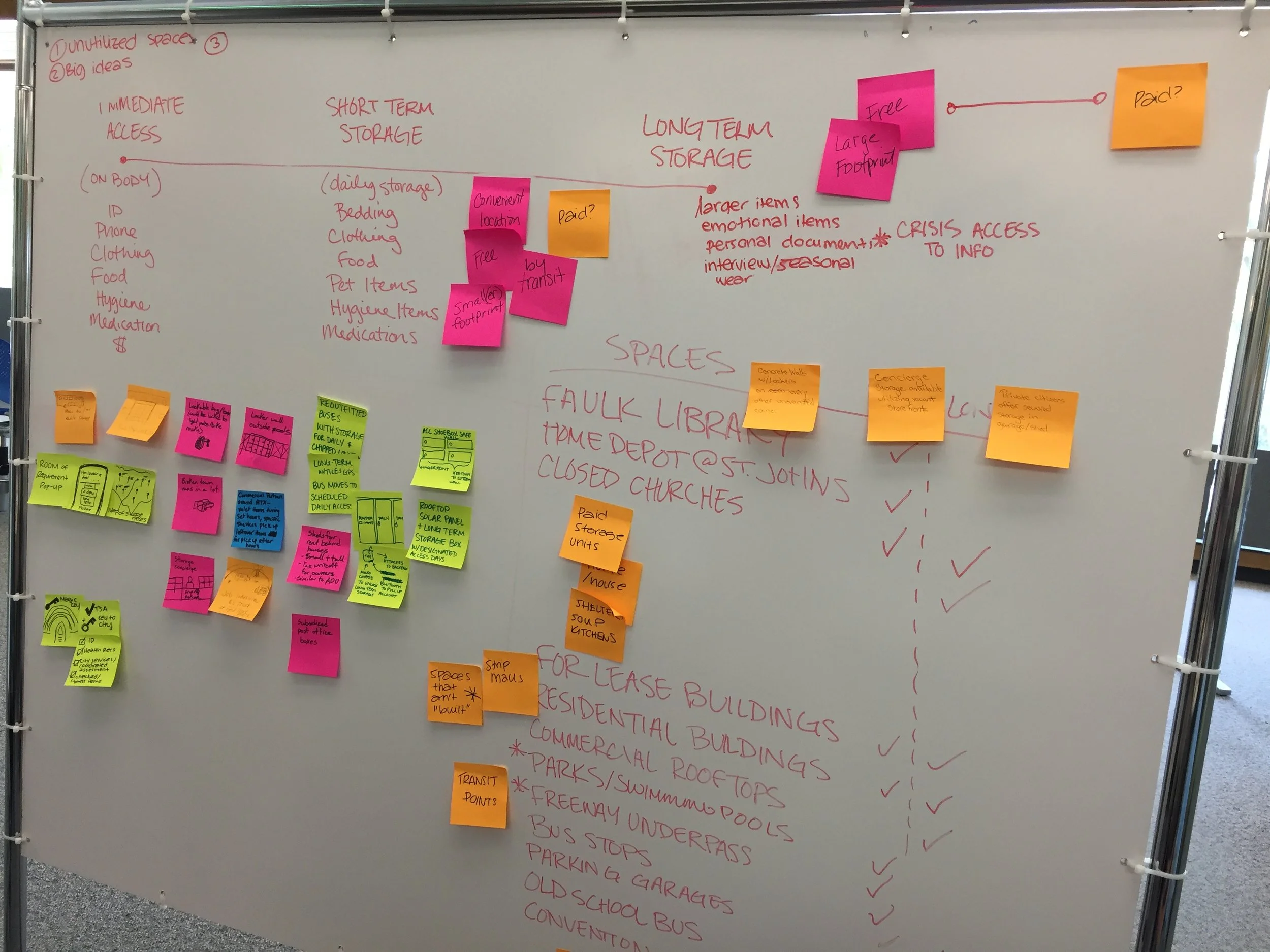

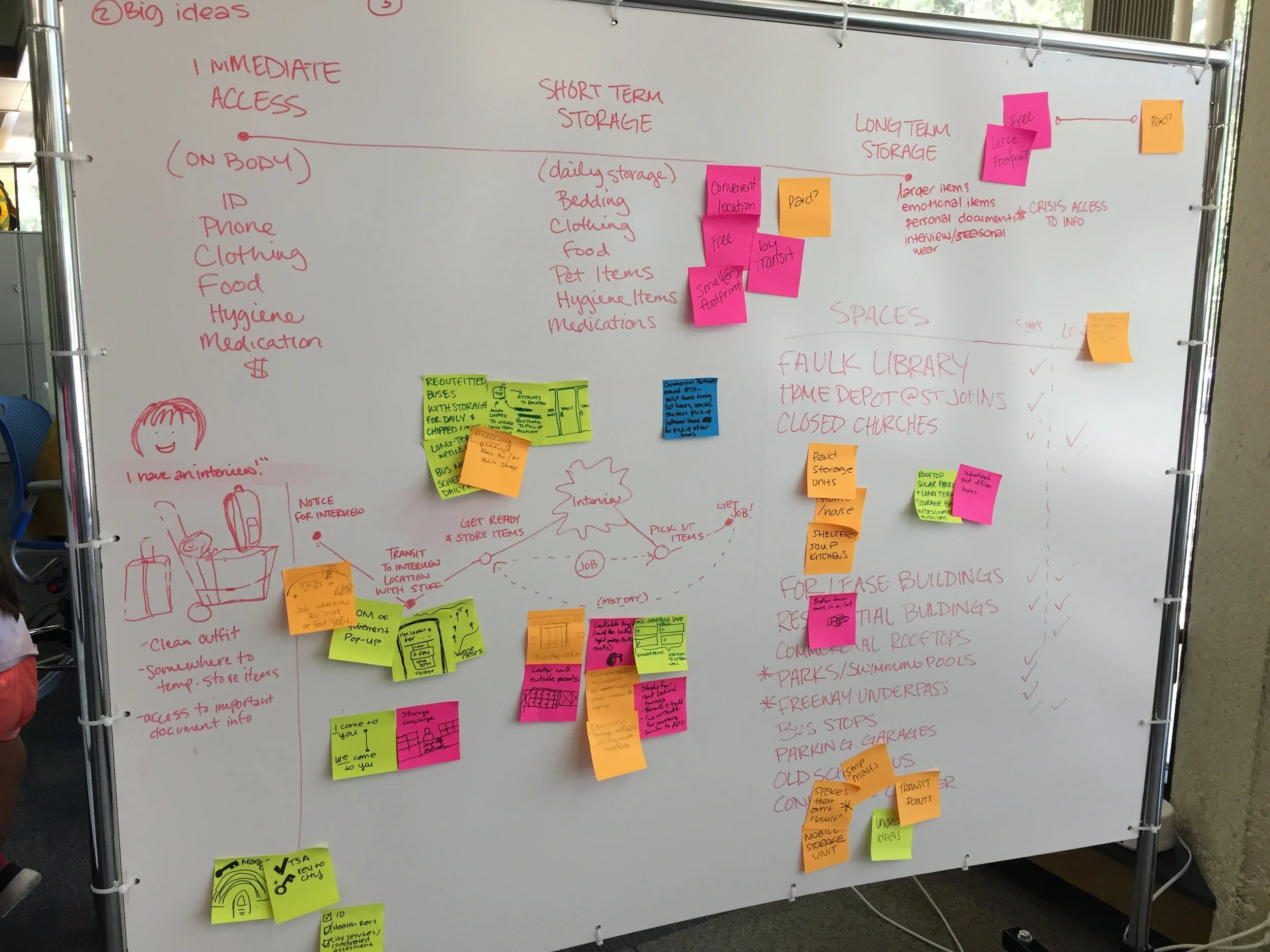

We began Saturday morning with this nugget and started by categorizing different types of storage with a person with lived experience. From this, realized the most impactful intervention might be with short-term storage, e.g. a place to store belonging to go to a job interview. We heard about Michelle* had to forego an interview because carrying her belongings with her to the interview site was too exhausting. We also heard the desire to present a clean presence and to not show any sign of being homeless, an impossible task while carrying their packs.

We considered the cities unused spaces, including the old Faulk Library building where we sat. We soon broadened our definition from buildings and solid structures to lots and buses, when we arrived at our big idea: Outfitting old school buses with lockers.

“Lockers on Wheels” seemed shockingly simple, but fun. So why didn’t this already exist?

Safety is a clear concern. How were we sure stored belongings weren’t dangerous or used for criminal activity? Also, what about the process of getting a locker — assault at the Austin Resource Center for the Homeless (ARCH) over lockers and in that space is anecdotally abundant. How would we prevent this from becoming the scenario at our storage buses?

Storage can be an eyesore and seen as a value detractor for property values. It would be unlikely for a company to dedicate an empty lot or building if it were to detract from their ability to sell or use it for a commercial purpose.

Dave* validated these concerns when he came by to hear our idea and immediately told us, “ this is never going to work.” He told us from his experience at the ARCH, people will take over the lockers and use as much storage as possible in a hoarding-like behavior. How would we prevent it from becoming a drug dealing location or prevent assault in the mad dash to get a locker? We took his experiences to heart as we began designing how this might be a safe, effective storage solution.

To build our prototypes, we used existing lockers in the space, tables, and wheels drawn on paper for low-fidelity versions of our bus. Our leaders also challenged us while prototyping to not just design a service, but to consider how in implementation, it might be a catalyst for lasting change, based on work with Sarah Shulman from InWithForward.

We developed two, taking into consideration the noted concerns and thoughts on how they might be more than a service.

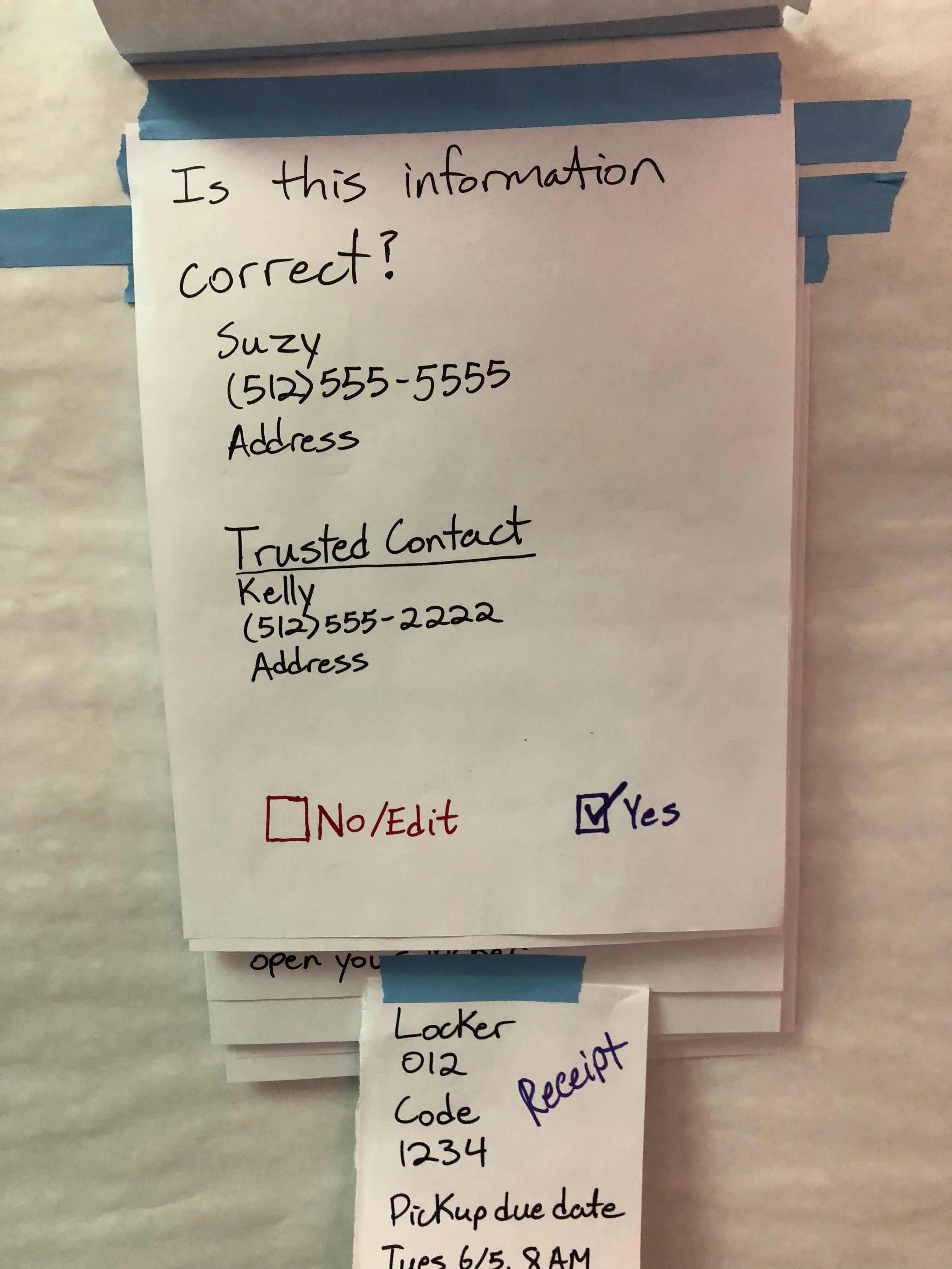

- A manned bus with lockers inside: People place their belongings in a provided clear bag and hand it to the bus attendant to store in a secured locker. They are provided a receipt with the location of where to pick up their belongings, in the event they surpassed the day limit of use.

- A bus outfitted with automated storage on the outside: A more extensive solution, this bus is similar to Amazon Lockers and simply requires swiping a MAP card (an ID provisioned at the ARCH) to open a locker and store their belongings. They can collect their items within 24 hours by simply swiping their card — no need to remember a combination or lock.

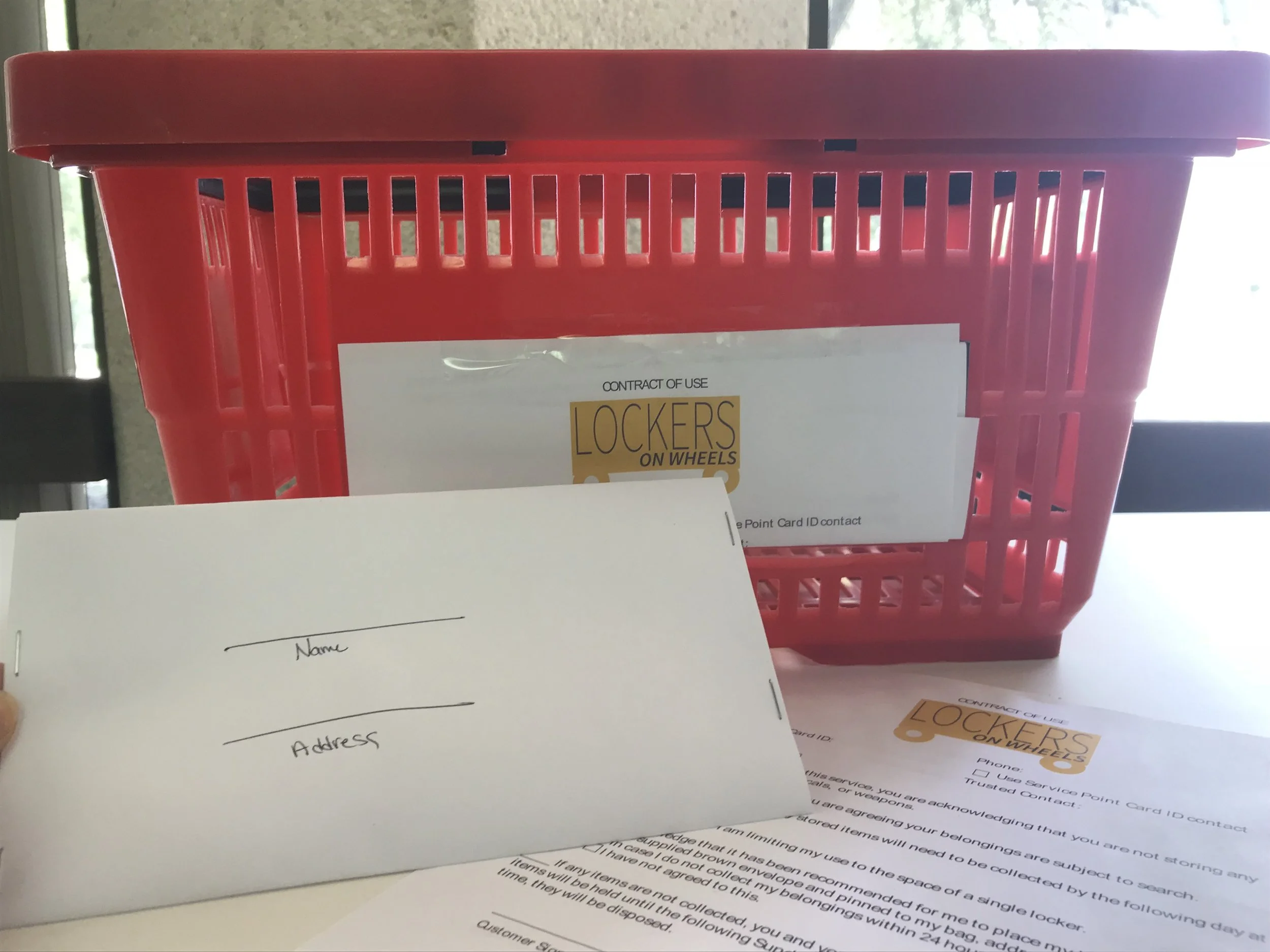

We presented a simple contract of use in each to be transparent about what was expected and start building trust, with the acknowledgement that dangerous or illegal items were not being stored and we had the right to search any belongings for safety reasons. Our collaborators with lived experience agreed this was valuable in maintaining safety and building trust with the community.

It is very possible that belongings could be left beyond the agreed pick up time. Currently at the ARCH, items are immediately thrown out to make room for the next user — they don’t have space to store them. We wanted to extend an element of grace to our users, partnering with a local church for 48 hour holding before donation. We also provided an envelope for personal documents to be self-addressed, and in this scenario, they would be mailed to ensure at the very least, they had their most precious items.

We initially thought the manned locker-bus would be the initial MVP to functionally test on the street, with the automated locker bus being the ideal state. Testing with Michelle and Sam* showed us our bias for technology in design and where a minimum viable product might hold the most valuable part: people.

The Lockers on Wheels team with big, tired post-presentation smiles

We wrapped up on Sunday with a presentation to the leadership team, several HACA residents, and people currently experiencing homelessness. I was touched to see heads nod in agreement to the articulated insights and uplifted to see faces shift from concern to delight as we shared Lockers on Wheels. Dave talked to me after the presentations, saying how far our team had come from Saturday afternoon when he thought it was a bust.

Over the last week, I’ve mulled over what those few days taught me. Of that list, I found:

Automation isn’t everything. As Dave said to the group during Saunday’s closing, “if I’m walking down the street, please don’t take three steps to the side to avoid me. Shake my hand and say hi.” A person’s financial status should not dictate their allowance of human acknowledgement, yet we do it all the time. A human touch or even a chance for positive and dignifying human interaction can be just as valuable as providing a functional service.

Our initial “first round” prototype of a bus with an attendant may be the more humane, powerful solution. When Sam tested this scenario, he commented on the benefit of being able to build a relationship with the attendant, in the case that he forgot his locker receipt. He was known, seen, remembered.

In addition, we realized this point of contact could serve as an additional point for disseminating information about resources and signing people up with the MAP card, a way to track homeless services use and build points with the system.

Digital is scary. The internet is still incredibly young when you look at a person’s lifespan. Without access to the past ten years of technology, a screen interface might as well be in a foreign language. Phones are surprisingly plentiful among the homeless, with programs that freely distribute them, but they are still used as phones. Most are non-smart phones and several people voiced their limited literacy, even with texting.

We might live primarily in a digital world, inside social media apps and using Google Maps to get anywhere, but many of the homeless population (and many people outside the US) still live primarily in the physical world. 46% of the world population still doesn’t have a connection to the internet.** Receipts, signs, conversations in person are valuable and needed. I found this to be inspiring and fresh — how human.

It’s okay to be affected. It’s important to be resilient as a designer — testing our concept and hearing Dave immediately reject it stung, but by listening, we were able to use his critique to shape something that worked. As much as it stung, it was critical to understand this is his life. His everyday.

On a deeper level, it was understanding that this could be me. I am not so different from anyone I met that weekend. People became homeless through medical issues, family tragedy, or bad luck — all possibilities for each one of us. The same concern I might have for things working for me is the care to have in designing for and relating with these users.

The stigma attached to people who appear homeless and shame in experiencing it is a tragedy, but one we can mend with a conversation, a smile, an acknowledgement that we are all humans, more similar than we are different. From that place, we can begin to look at our contexts of existence and ask “how might we restore and renew Austin’s people?”

The Service Hustlers for Homelessness

- *names have been changed to protect identities

- **https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IT.NET.USER.ZS